“What people believe prevails over the truth” – Sophocles, The Sons of Aleus

Among the societal preoccupations and political wedge issues that have pervaded American culture, none is perhaps free from the entanglement and securing of the right to openly speak one’s opinion. The right to free speech is one of America’s most cherished and revered principles. It maintains the open marketplace of opinions and ideas that drive our social and political discourse; its role in American society is unrivaled, for it protects the public’s accessibility to the fundamental principles of liberty and equality. And yet, it would appear that this right has recently proven to have drawbacks, namely in facilitating the very divisive social climate that the American people find themselves within in 2017: one preoccupied with racial tension, political polarity and recalcitrant sentiment, misguided accusations of immorality; and the endurance of a social atmosphere void of mutual respect – an actualized culture war that is evolving from a “post-truth” era.

The concept of a “post-truth” era is relatively new in name, but its hallmarks can be identified throughout history. A post-truth era is entirely catalyzed by demagoguery, rhetoric, and an appeal to innate and primal tendencies of human behavior. Certain personalities are predisposed to this behavior; those who establish a Machiavellian public image, whether consciously or unconsciously, utilize traits of egotism and duplicity to garner a popular following based in persuasiveness and potency. Further, a post-truth era’s social and political climate heavily neglect objective fact in order to shape popular opinion. American culture has progressed to a point in that political leaders now have the option to take advantage of the fallibility of man. Espousing lies and false Cassandras to shape public opinion is now a reality. The truth has become blurred and the conflation of a dyadic relationship has integrated itself into political dialogue: the truth becoming a lie, a lie becoming the truth.

A dyadic relationship between truth and falsehoods is not exclusive to these virtues: love and hate, good and evil, light and dark, animus and anima all find universal meaning from their respective dyadic relationships. These ideas would come to be supported by the psychological research of Carl Jung, who observed and recorded these relationships across historical, literary, and artistic mediums. The ancient Greeks, as a matter of fact, were particularly fascinated in assessing the value of dyads, especially wisdom and ignorance throughout human nature. These relationships pervade human nature and exist in various forms. In today’s political landscape though, the concept of “truth” has been taken for granted and handled irresponsibly, ultimately being used to sway public opinion and to consolidate popularity.

The idea of “truth” and the virtue of wisdom has been held in question throughout history, especially during the Classical Greek period. Plato, for instance, describes Socrates’ encounter with a post-truth phenomenon in The Apology. Socrates argues with a politician who claims to be wise and, when Socrates begins challenge his claim, both the politician and several engaged bystanders become angry and hateful of Socrates’ prying. Of course, this is not to say Socrates’ inquisitions was not valid; the ancient Greeks were fond of argument and debate within the agora as a part of their culture. But Plato’s description of this encounter goes beyond a simple disagreement between two individuals; rather, he describes a confliction of virtue – of wisdom and ignorance – that generates greater hostility when compared to a simple difference of opinion.

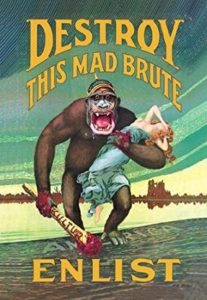

This is seen throughout American history. The freedom to speak and to organize around those with like ideas and opinions has driven political discourse since the drafting of the Constitution. Yet once a faction seizes on a falsehood that people can perceive as truth, positions are entrenched more vehemently and our culture begins to sway and waiver. Factions that have historically advocated for these falsehoods as platforms carry many similarities to America’s current sentiment. The nativist sentiment pushed by the American Party, or the “Know Nothings,” purported ethnically charged lies about Irish and German immigrants; the domination of American culture by wartime propaganda throughout the World Wars that was particularly aimed at the Germans and the Japanese, displayed the government’s ability to take hold of and manipulate popular opinion; and even the fear-mongering sentiment of McCarthyism showed the extent at which government can pursue accusations without proper evidence. How can one say that our current situation is so unique when American culture thrives off of biases and skewed positions?

Interestingly enough, our current situation is unique; though historians can reflect on the past travesties of America’s culture, they are currently disavowing our present circumstances, essentially history repeating itself. And although the past and current sentiments may have been justified through ideas like patriotism and national security, a consensus has been drawn that at present this sentiment is proving a danger to America’s institutions, namely the abuse of the right to free speech. A clear example of this is an interview between then-candidate Donald Trump and conservative talk show host Hugh Hewitt; in this interview, Trump openly lies in asserting that then-President Obama had created the terror organization ISIL, affirming his no-nonsense, “tells-it-like-it-is” branding. Trump has manipulated America’s past sentiment and morphed it into a post-truth phenomenon, modifying it in a way that is impervious to any form of argumentative dialogue or debate, for it only fuels the haste and passions his followers.

To his credit, it would appear Trump’s campaign style depended upon the successful manipulation of mass media outlets like CNN, Fox News, and the New York Times. Whether his un-statesmanlike behavior was a strategic campaigning style or that his blunt statements carried his voting base, the mass media outlets’ coverage of the Trump campaign provided with about $2 billion worth in extended news cycles by February of 2016, despite the Trump campaign only spending about $10 million in advertising. Trump himself, as a prelude to his eventual Presidential run, remarked in the late 1980s that being “a little different, or a little outrageous” attracted the press. He would come to capitalize on this idea of political differentiation from a field of establishment candidates and built his platform that legitimized outrageousness and falsities, eventually manipulating the media to project the message.

And where do we go from here? American political culture is faced with a breach of precedent, accompanied by hyper-partisanship, ideological differences, and divisive rhetoric. Unfortunately, this has engendered an environment in which many organizations and institutions have resorted to restricting free speech as an instinctive measure. In a recent Pew Research Center poll, 40% of Millennials who responded claimed that they were in favor of restricting free speech through government censorship if the speech was considered offensive to minority groups. It’s a natural inclination to silence divisive opinions and ideas through government intervention as well as, more informally, social dismissal. Yet, this is not conducive to American culture for it limits the freedom, equitability, and accessibility to the right to freely speak. If an opinion has proven to be wrong, the open-market of ideas will deem it as so, without need of censorship.

Upon reflection, it is necessary to ask: what does the truth provide us? Plato, for instance, insinuates within his Allegory of the Cave that it is an ideal “form” to strive to achieve. This may hold some validity, but this proposition does not take into account the value of argument and debate, despite this process being integral to ancient Greek culture. John Stuart Mill, however, does write extensively about open dialogue as well as the benefit of free and open discourse in his essay On Liberty. He contends that the advantages of open dialogue is far more beneficial to an individual’s given potential compared to a society of restricted speech or false opinion. Mill writes:

“Men are not more zealous for truth than they often are for error … it [truth] may be extinguished once, twice, or many times, but in the course of ages there will generally be found persons to rediscover it, until some one of its reappearances falls on a time when from favorable circumstances it escapes persecution until it has made such head as to withstand all subsequent attempts to suppress it.”

Mill perceives the looming threat of falsehoods in a society of free and open dialogue, and purports that only time and engaged dialogue can reveal the advantages of free speech. Although this post-truth phenomenon is seemingly void of any logical dialogue, the presence of dissent and opposition is a healthy reaction when effected through a comprehensive dialogue.

In reality, it seems American culture has diverted from Mill’s quintessential society. Racial and ethnic tension, political divisiveness, and an acute lack of empathy pervades our culture, enabled by our social media platforms. Bret Stephens, a New York Times columnist and a recent recipient of the Lowy Institute Media Award, described the social climate in the United States in a recent lecture. He describes that American dialogue and, more particularly, dissenting dialogue is readily toxic in that:

“we fight each other from the safe distance of our separate islands of ideology and identity and listen intently to echoes of ourselves. We take exaggerated and histrionic offense to whatever is said about us. We banish entire lines of thought and attempt to excommunicate all manner of people … without giving them so much as a cursory hearing.”

This is what is allowing America’s post-truth era to flourish. Individuals form and hold opinions and do not challenge people openly and publicly – they limit their dialogue to the social consolidation and anonymity of the internet. The freedom of speech coupled with mass and social media has generated a culture of intense ideological siloing of individuals that do not truly engage and quash false ideas. Consequently, a sizable amount of individuals are left accepting lies and ignorance as truth.

In this present time, the freedom to openly argue and debate is an influential weapon to wield. Its comprehensive, logical, and if used effectively infallible. It is no surprise that it has been utilized in all aspects of public life, for it is the arrow to society’s target. And as new obstacles present themselves, such as the rise of fringe factions like the neo-Nazi party, anti-semitism, racist and bigoted factions, or any faction that is not representative America’s inalienable principles, understanding the value of unrestricted public discourse is monumental.

For leaders that perpetuate a phenomenon in which objective falsehoods, their time in power is — to Mill – ostensibly numbered. These leaders peddle demagogic rhetoric only to have it fall out of the graces of popular opinion soon after. But only the freedom to openly, respectively, and empathetically express dissent to others is how individuals can combat a post-truth phenomenon. Consider former President Kennedy’s inaugural words in the face of today’s post-truth era: “those who foolishly sought power by riding the back of the tiger ended up inside.” President Trump may have modified the political playbook, but it may be accompanied by drawbacks. Trump has interestingly played off of the emotions of Americans rather than objective fact. Emotions are dynamic and volatile; only time will determine Trump’s perception by the public, considering his support, in its entirety, is established off of emotions.

As American culture develops it is invaluable to understand these moments in time. Not only is it crucial to acknowledge that a post-truth society was enabled, and that truth and falsehoods were easily manipulated and conflated, but also how it was facilitated and what were the priming variables. Partisan polarization, ideological consolidation, association based in uniformity rather than diversity, have become symptoms of a post-truth era and should be considered in the future. Freedom of speech, though it appears to have been a major influence in this problem, has also shown to be a powerful way to overcome the natural tendency to trust in human emotion and impulse rather than objective fact. But until American society understand this value, only time will tell if American culture will understand the dangers of a post-truth era.